February 12 to April 24, 2005

Hanksville

A couple of years ago, I wrote a narrative for Blackflash magazine called The Wandering Boy. In this piece, I attempted to explain, through text and images, what I think my activities as a writer and producer of museum exhibitions is about. I spoke of my process as one of constant wandering that involved collecting, documenting and the scripting of highly personal narratives. I spoke of the kinds of places that I have consistently been drawn to — the fringes of the urban, forgotten towns, abandoned industrial sites and the faint traces of failure. I didn’t use the name at the time, but these places are Hanksville. Hanksville, “my” Hanksville that is, is not a specific location; it is more like a spirit or a feeling.

Actually, there is a “real” town called Hanksville and it is from this town that I took the name that I now use to define the diverse range of sites that I have wandered through and sampled over the past decade. This “real” Hanksville is in Utah. It is an isolated and forgotten little town at a crossroads in the middle of a dry desert. It was where the highways met and, like many such points throughout North America, it was supposed to prosper. But no one stopped, and so few businesses ever came. (Recently I checked out the town’s website, it was blank, just a cryptic message — “This site is under construction.”) I liked the name of the town because it suggested Hank Williams and a history of hope, tragedy and failure captured in classic country music. Hank Williams, Emmett Miller, Roy Orbison, this is the soundtrack of Hanksville, a haunting high lonesome sound.

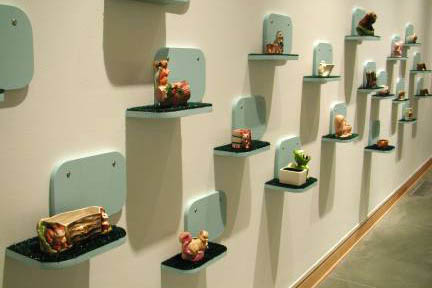

Over the past few years, I have traveled extensively visiting sites, archives and local museums. Places like the abandoned La Colle Falls Dam on the outskirts of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan and the subtle traces of the Chignecto Ship’s Railway built to move boats from the Northhumberland Straight to the Bay of Fundy. I have visited the rotting remains of the Gilmour Lumber Companies failed flume scheme in Algonquin Park and documented the remnants of the Desjardin’s Canal just outside my old studio in Dundas, Ontario. I have visited a number of Britain’s “New Towns” and explored hollow edifices of China’s Cultural Revolution. I’ve wandered many World’s Fair sites that today sit idle, their futuristic visions now all peeling paint, broken glass, decaying metal and crumbling concrete like the all too numerous sites of tragically flawed urban renewal that many of these fairs inspired. Then there are the flea markets and junk shops where I have found the artifacts of Hanksville. All of this, and much more, have fueled the creation of an evolving installation originally presented by the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon.

But Hanksville is not only about the past. For me, in fact, its most harrowing traces permeate the present. I look for signs of “progress,” aggressive transformations of the landscape, bold industrial schemes and civic urban policies that are rarely binding laws but are more often simply bargaining tools for cities mired in alliances with developers. This is particularly evident in the sprawling “Golden Horseshoe” of Southern Ontario where I live, but it is echoed across the country and throughout the “developed” world and is so often the model the “developing” world aspires to. Typical of my work, Hanksville looks at the present through the lens of the past. I see this as a counter to a kind of persistent futurist faith in the new, our ability to design perfect environments, to “fix” our mistakes and improve the natural world we have been shaped by. I have been called a pessimist. Its is a label I am afraid I cannot, but wish I could, deny.

Like many of my installations, Hanksville includes commissioned art works, in this case a new series of photo-based works by Winnipeg artist William Eakin. The publication for the project is a dedicated issue of Blackflash magazine that includes my extended illustrated narrative along with Eakin’s images, an additional commissioned work by Adriana Kuiper and complementary projects by Diana Savage and Jillian McDonald. This represents a parallel version of the project developed in an alternate narrative space that allows me to explore both the same terrain as the installation while projecting out into other, often imagined, places in a dialogue with invented characters.

Hanksville in Kelowna

As with all of my exhibitions, I try to draw the local into each manifestation of a project. I have approached Kelowna through the lens of Hanksvillle, first looking for a historical model and then wandering the landscape for contemporary signs. Thanks to Wayne Wilson at the Kelowna Museum, I came across the story of the failed Okanagan Oil and Gas Company Limited (circa 1930). Exploring the terrain of the town and its surroundings, I documented the remains of one of Vancouver’s Expo 86 pavilions along with numerous recent developments. I am sensitive to the fact that I am obviously not a local, that some may feel I have no right to pass through town and cast such a pessimist’s eye on the regional proceedings. Fair enough. In defense, I will say this: I do not consider myself wholly an outsider anywhere I pass through. Now, more than ever, what is done locally resonates nationally and globally and what happens here has significant external influences and equally echoes back out to the broader world.

Andrew T. Hunter

Andrew T. Hunter is an independent artist, writer and curator based in Dundas, Ontario. His narrative-based work draws on public and private collections and emphasizes a highly personal engagement with history and ideas of place. He has held curatorial positions at the Art Gallery of Hamilton, Kamloops Art Gallery and Vancouver Art Gallery and has been Adjunct Curator with the Confederation Centre Art Gallery and Museum and the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. His projects have been presented by art galleries and museums across Canada, in the United States and England.